TL;DR

It’s a free browser-based simulator where you can build, wire, and run circuits without buying parts (or worrying about breaking anything).

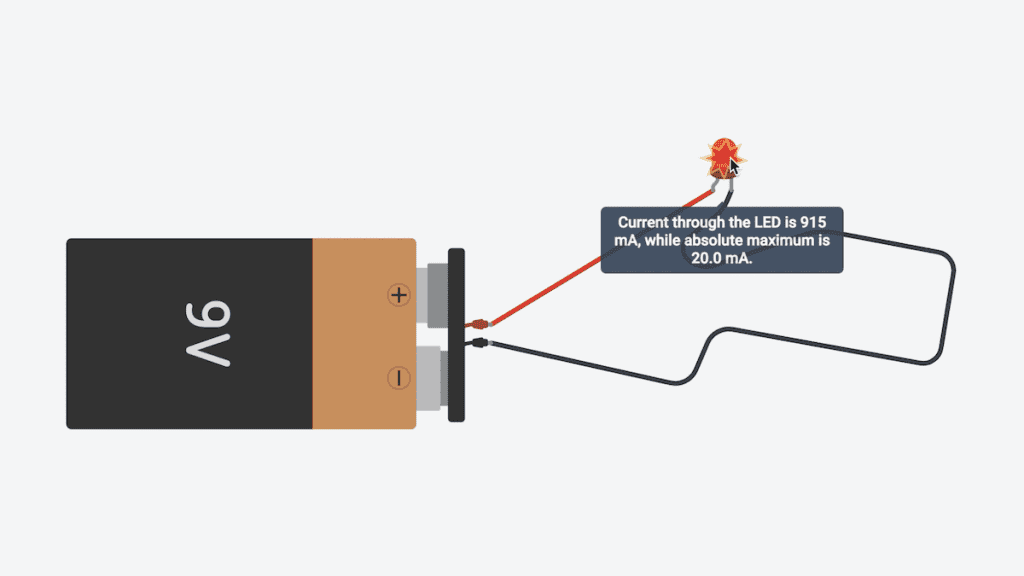

Connecting an LED to a 9V battery without a resistor pushes too much current, so the LED “pops” in the simulator (and would likely fail in real life).

Add a resistor in series so the LED gets safe current, then tweak resistance values to see brightness change in real time.

A switch opens/closes the loop so you get real control instead of a circuit that runs immediately when you hit Simulate.

Ever wanted to make an electrical circuit, use batteries, LEDs, wires, stuff like that, but you didn’t know how to get started? 🤔 Maybe you looked at a soldering iron and thought, nah. Or maybe you just didn’t want to spend money on parts you might fry.

Tinkercad is a free tool that lets you learn all of that stuff without getting your hands too dirty, without having to solder, without having to actually own any of the parts. And honestly it’s one of the best ways to learn because you can break things on purpose with zero consequences. 👍

If you’re brand new to electronics and want to understand the basics, our intro to Tinkercad Circuits covers how the platform works and what makes it so good for beginners. It’s a great starting point if you want the bigger picture first.

So here’s what we’re gonna do: I’m gonna show you how to light an LED in Tinkercad, step by step, and we’re gonna do it the wrong way first. On purpose. Because watching a virtual LED explode teaches you more about resistors than any textbook definition ever could.

Learn to create a circuit with Tinkercad

What Is Tinkercad and Why Should You Care?

Tinkercad is a free, browser-based tool made by Autodesk. No downloads, no installations, no credit card. You just sign up and start building. It’s got sections for 3D modeling, coding, and the one we care about, Circuits.

The Circuits section gives you a virtual workspace where you can drag in components like batteries, LEDs, resistors, switches, and even Arduino boards, wire them together, and hit “Start Simulation” to see what happens.

If something goes wrong, nothing actually breaks. You just reset and try again.

That’s the whole reason I love this thing for beginners. It’s gonna be really easy and simple, and I’m gonna show you every single thing that we’re doing step by step so that you can start creating your very own electronics for free today.

Tinkercad Interface

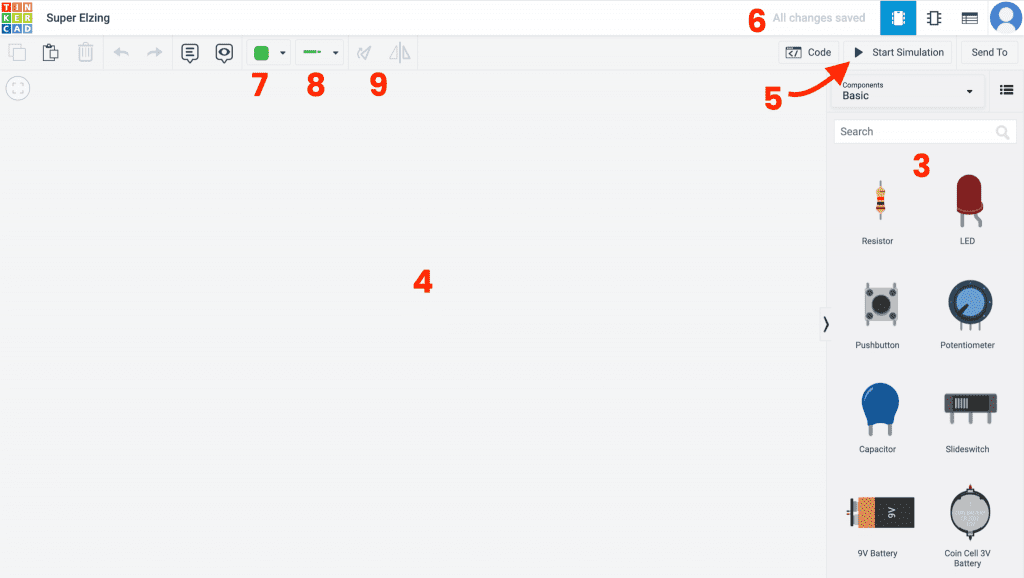

Before we begin, let’s take a quick tour of the tinker cad interface.

Below, I list the tools and areas we will use for this project.

- Project Type selection panel – Select the type of project you want to make (3d modeling or electrical circuits)

- Create a new project – Creates a new project

- Components panel – A list of all the components available

- Workspace – the area you will drop your components on.

- Run simulation – Start and stop the simulation

- Autosave – Signifies that the autosave feature is enables

- Change wire color – choose this to change the color of a wire

- Change wire connection type – choose this to change the wires connection type

- Change component orientation – Rotates the component

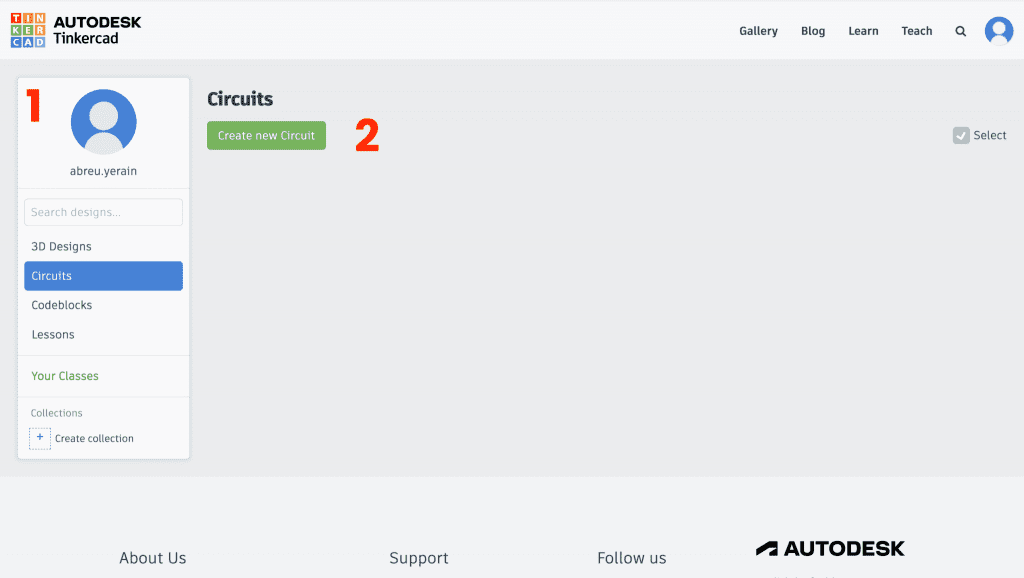

Step 1: Set Up Your Workspace

Head to tinkercad.com and log in. On the left side panel you’ll see 3D Designs, Circuits, Codeblocks, and Lessons. Click on Circuits, then hit Create new circuit.

You’ll get a blank workspace on the left and a component panel on the right. That right panel is basically your virtual parts bin, everything from resistors to sensors, all free, all unlimited.

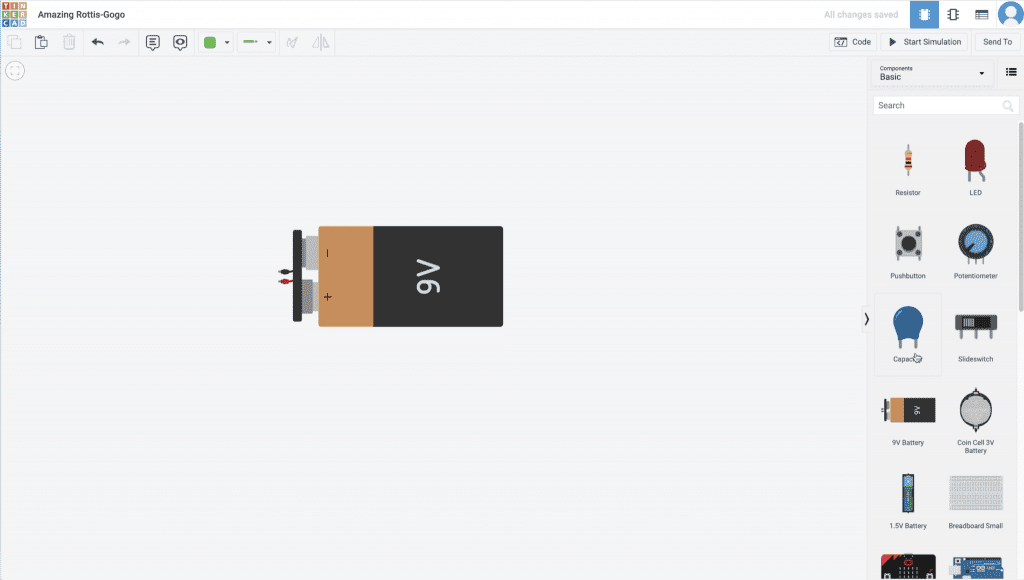

Now grab a 9-volt battery from the component list and drag it onto your workspace. You could use a 1.5V battery or a coin cell, but I like the 9V just because it’s got that Duracell look and it just looks very battery-ish. Rotate it however you want.

Next, drag an LED onto the workspace. That’s it for now. Two components. Let’s see what happens.

Step 2: Blow Up Your LED (Yes, Really)

Before we do anything smart, we’re gonna do something dumb. On purpose. This is the fast way to learn.

Wire the LED directly to the battery. Connect the anode (the longer leg, the bent leg, which is the positive terminal) to the positive side of the battery with a wire, and the cathode (the shorter leg, the negative terminal) to the negative side. Polarity matters on LEDs.

Use wire colors consistently: red for positive and black for negative. In Tinkercad, click a wire and press a number key to change its color.

Now hit Start Simulation. Too much current. It exploded!

Your LED just popped.

The 9V battery shoved way too much current through that little diode and it couldn’t handle it. This is exactly what would happen with real components, except you’d be out a few bucks and maybe a little startled.

So what did we learn? We need something to limit the amount of electricity running to the LED. We need a resistor.

Step 3: Add a Resistor (and Actually Understand Why)

What is a resistor?

A resistor is exactly what it sounds like. It resists the flow of electricity. Resistors have values denoted in ohms, the Greek letter for Omega. The values are also color-coded right on the LEDs. See those different colored stripes? That’s a visual representation of the ohm value.

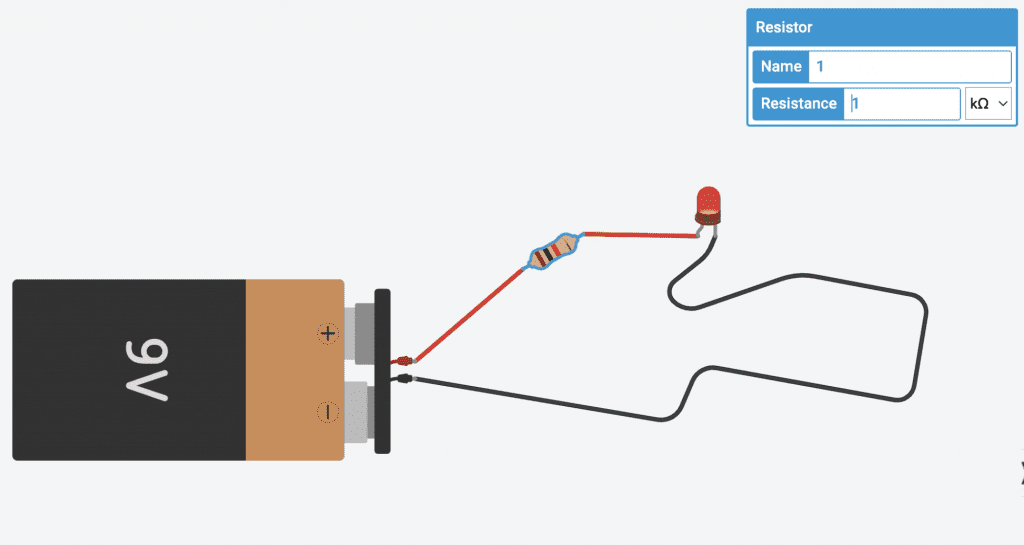

To know what ohm value your resistor has. You can actually click on the resistor and change the resistance values, and as you do that, you’ll notice that the colors also change.

Let’s go ahead and grab a resistor from our components panel.

So what’s a resistor actually doing here? A resistor does one job: it resists the flow of electrical current. It takes the amount of electricity coming from your power source and turns it down so your components don’t get overwhelmed.

Think of it like a valve on a garden hose: the water pressure (voltage) stays the same at the source, but the valve controls how much water (current) actually flows through.

The relationship between voltage, current, and resistance is described by Ohm’s Law: V = I × R. You don’t need to memorize the formula right now, but just know that increasing resistance means less current flows through your circuit. That’s the whole point.

Fun Fact: Resistors use colored bands to indicate their value. As you change the resistance in Tinkercad, you’ll see the colors on the virtual resistor change in real time. It’s a built-in cheat sheet.

Wiring It Up

Stop the simulation. Delete the wire connecting the battery’s positive terminal directly to the LED. Now drag a resistor from the component panel onto the workspace and place it between the battery and the LED. Put it in series.

- Battery positive terminal → Resistor (either side; direction doesn’t matter)

- Resistor → LED anode (positive leg)

- LED cathode (negative leg) → Battery negative terminal

Make your positive-side wires red and your negative wire black. Start the simulation. The LED should glow.

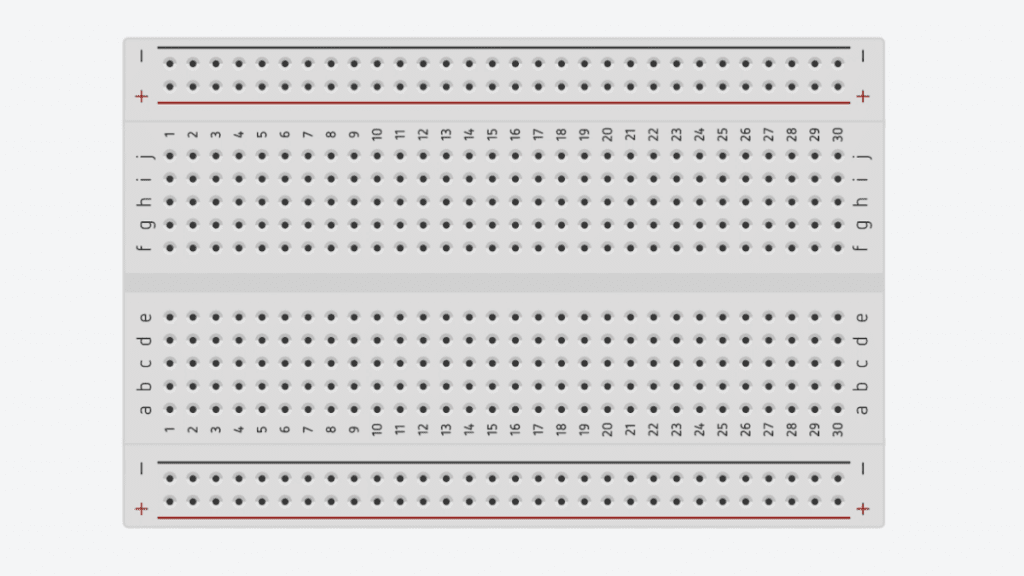

What is a breadboard?

A breadboard is a small flat surface that allows you to connect electrical circuits with ease. There is no soldering required, and everything is laid out in a grid-like fashion, making things clean and easy to work with.

The red line denotes positive, and the black indicates negative. These are, of course, not positive until you make them positive or negative by connecting them to your power source.

If you hover over the positive and negative terminals you’ll notice that the whole rows turn green. This is to signify that The rows are interconnected. Similarly, if you hover over the inside of the Bread Board, you will notice that the internal rows light up green as well. These are also interconnected, so if you connect two things in this row, they will all be connected, the same as soldered together.

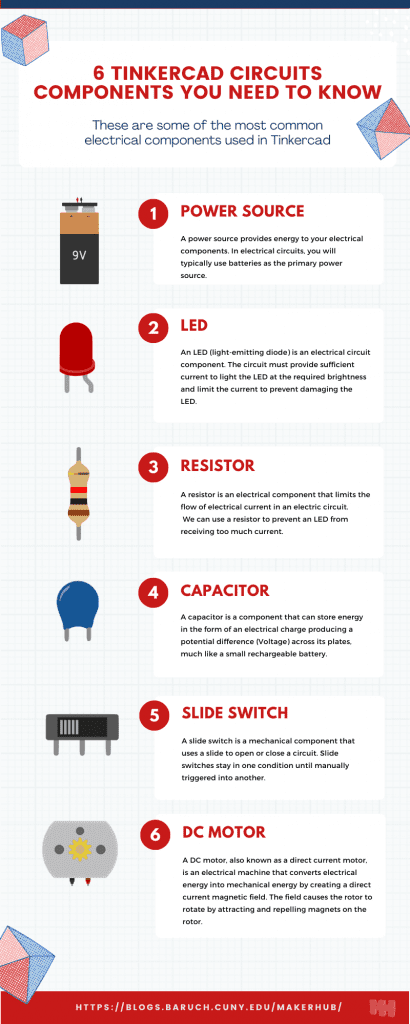

Common components

Check out this infographic that shows the most commonly used electrical components.

Dialing In the Right Resistance

Now here’s where it gets fun. Click on the resistor while the simulation is running and you’ll see a value field; it defaults to 1 kΩ (kilohm, which is 1,000 ohms). Try changing it and watch the LED brightness respond.

| Resistance Value | What Happens |

|---|---|

| 1 kΩ | LED glows nicely |

| 10 kΩ | It gets real dark |

| 100 kΩ | It pretty much turns off; you’re limiting the electricity way too much |

| 0.1 kΩ (100Ω) | Warning appears (likely too much current) |

| 0.4 kΩ (400Ω) | Bright but safe; a good spot for a 9V setup |

So it seems like 0.4 is the safest we can get before this pops. That’s the value I’m keeping.

If you’re building this with real components, a common safe resistor value for a standard red or green LED powered by a 9V battery is around 330Ω to 470Ω, depending on the LED’s forward voltage and current rating. Many standard LEDs max out around 20mA, so use Ohm’s Law to calculate resistance (and consider using a higher value for a safer margin).

Step 4: Add a Switch for On/Off Control

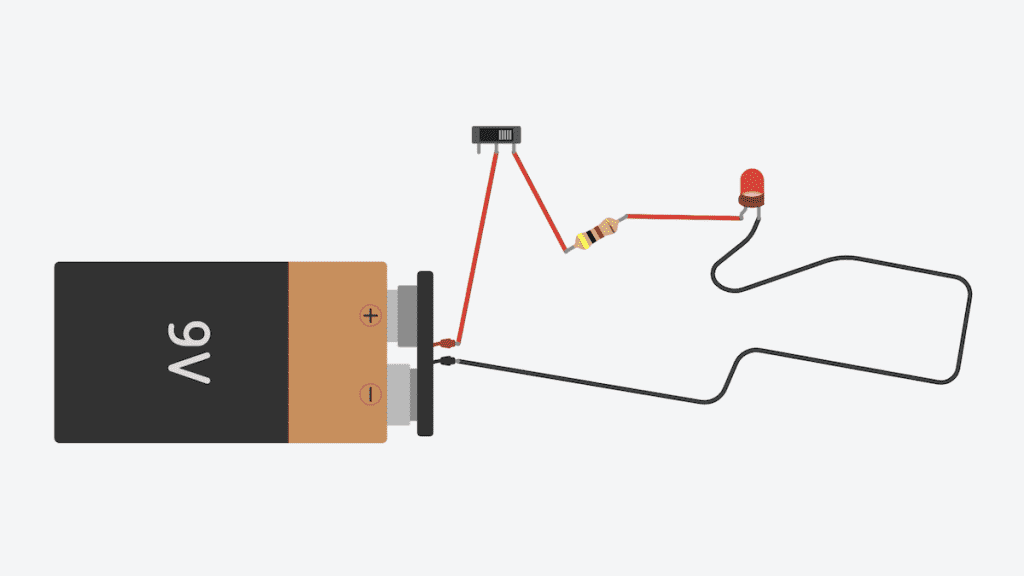

Right now the circuit runs the moment you hit simulate. There’s no way to turn it on and off. It’s just going to run perpetually all the time. We don’t want that.

So let’s add a slide switch. Stop the simulation. Delete the wire going from your battery’s positive terminal to the resistor. Drag a slide switch onto the workspace and place it between the battery and the resistor. Now you’ll control the loop.

- Battery positive terminal → Middle pin of the slide switch

- One outer pin of the slide switch → Resistor

- Everything else stays the same

The purpose is for this to close the circuit. When you click it, it’ll connect one side to the other. Right now it’s empty, it’s not closed.

Electricity needs a complete loop (a closed circuit) to flow. A switch breaks or reconnects that loop: open = no current, closed = LED on.

Start the simulation. The LED should be off. The circuit is open.

Now click the switch. And the light turns on. Amazing!

Click it again. Off. On. Off. On. That’s on/off control.

That is how we turn on an LED, a basic LED with some basic components. This is really simple stuff, and it’s something that you can have a lot of fun with.

Your Finished Circuit at a Glance

Circuit Summary

What You Built

- 9V battery as your power source

- Slide switch for on/off control

- Resistor (0.4 kΩ) to limit current

- LED that glows without exploding

What You Learned

- LEDs need resistors or they burn out

- Wire color conventions (red = positive, black = negative)

- A circuit must be a loop to work

- Tinkercad is zero-risk for experimenting

What to Try Next

Once you’ve got this working, mess around. Seriously. That’s the best part about Tinkercad.

Swap the 9V battery for a 1.5V battery and see what happens. Try a push button instead of a slide switch. Drag in an RGB LED and see if you can make it change colors.

Or try wiring two LEDs in parallel; our guide on series vs. parallel circuits breaks down how those work and why old Christmas lights were wired so badly. Experiment on purpose.

Look at all these items that you can use. All these components are totally free, obviously. They don’t exist. You can just use as many of them as you want. I encourage trying to experiment, just see what happens with different things if you try different things. Curiosity is the whole game.

Fun Fact: Tinkercad’s component library includes everything from basic resistors to ultrasonic distance sensors, gas sensors, and full Arduino Uno boards. You could build a complete interactive electronics project, like a light-sensing circuit with a photoresistor, without ever leaving your browser. It’s surprisingly powerful.

Frequently Asked Questions

Absolutely. Tinkercad offers 1.5V, 3V coin cell, and 9V batteries. If you drop to a lower voltage like 1.5V, you’ll need a much smaller resistor (or possibly none, depending on the LED’s forward voltage) to get the LED to light up. 9V is great for demos because the resistor’s effect is obvious.

Nope. Resistors are not polarized, meaning they work the same regardless of which way current flows through them. LEDs are polarized, so the LED direction matters, but resistors don’t care.

A slide switch stays in whatever position you leave it (on stays on until you flip it back). A push button only closes the circuit while you’re pressing it. Both open and close circuits, but one is momentary and the other is persistent.

Yes, and it’s actually pretty cheap. A 9V battery, a pack of LEDs, a handful of resistors, and a mini breadboard can typically be found for under $15–$20 total (prices vary). Test it in Tinkercad first, then use the LED datasheet plus Ohm’s Law to choose the right resistor.

Check two things. First, make sure your LED isn’t wired backwards: the anode (positive, longer leg in real life, bent leg in Tinkercad) must connect to the positive side.

Second, if you’re using a switch, make sure it’s actually closed. An open circuit cannot light an LED.

Final Thoughts

Using a TinkerCad circuit is a great way to learn how electronic circuits work. It’s free and really easy to use. And now that you know how to light up an LED on TinkerCad, you’re ready to start exploring all the other components the software has to offer.

The whole point of this exercise wasn’t just to get a little virtual light to glow on screen. It was to understand what’s actually happening when electricity flows through a circuit and why components like resistors aren’t optional extras—they’re the reason your LED survives. You learned by failing first.

There’s so much to learn in Tinkercad. It’s a really fun tool, and it’s a free tool, and I very much encourage you to poke around and look at all the components that they have.

So go mess things up. Swap parts, change values, blow up a few more virtual LEDs. That’s literally what it’s for, and every mistake you make in there is one you won’t make when you eventually build the real thing.